Sick Happens

by Campfire Head Coaches Molly Balfe and Chris Bagg

First, it's totally understandable that you're worried. You've been training hard throughout the spring, building your threshold power on the bike, improving your run endurance, and working on technique in the pool. Your first big race is coming right up, and you feel like you're on track for a strong performance. And then you get sick. You can't work out; you can't really get out of bed. You're out for at least a week. What do you do?

If you have been dealing with a cold or flu, the return to training is typically straightforward. There is a general guideline to follow with sickness, which we’ll lead with here: If you're sick, wait until you feel COMPLETELY NORMAL (100% back to normal), and then...WAIT ONE MORE DAY. Yes, you read that correctly. Wait until you feel perfect, and then wait another day. I can't tell you how many times I've told this to athletes, and then heard something like "Well, I think I'm OK. I've still got a bit of a sore throat and a runny nose, but I could probably train." A week later, the athlete still feels rotten, and the intervening week of training is pretty much wasted.

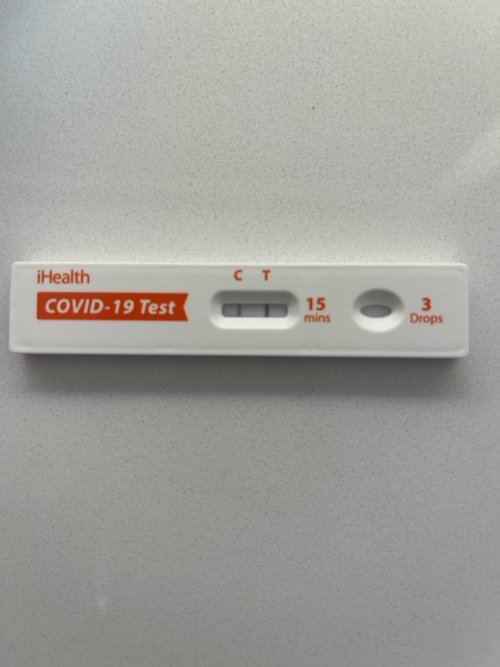

If you are coming back from from covid, it is wise to be a bit more cautious. So much is still unknown and there seem to be real risks of cardiac damage, especially in severe infections. The American College of Sport Medicine has some guidelines for returning to training, which include:

Athletes under age 50 who were asymptomatic or had mild respiratory symptoms that resolved within 7 days can follow a gradual return to exercise after resting for 10 days

Asymptomatic athletes should rest for 7 days

Athletes over age 50, or with symptoms (including shortness of breath or chest pain) or fatigue that lasted more than 7 days should be evaluated by a physician before returning to training.

All athletes should engage in 2 weeks of minimal exertion before increasing volume and intensity, and those increases should be gradual.

We get it. Not training feels calamitous. It feels as if you're sliding back into your pre-season lack of fitness. You've spent money on travel, on a race, on a coach. The thought of doing nothing is terrifying. And here's where we hope you'll learn something from this blog. The basic guidelines are simple, but the execution can be excruciating. Here's a chance to do some mental training, while you're sick.

1. Why is it excruciating? What about losing a week or so of training threatens your sense of identity as an athlete? Or, to put it more bluntly, what are you afraid of losing?

2. Now that you've admitted what you're afraid of losing, keep following that thread. If you lose that thing, what's next? What else will you lose? What's at risk if you take time off of training?

3. Keep heading on down the ladder, until you get to the very bottom. It'll probably be something you didn't expect, something like "people will know that I'm a fraud," or "everyone will be proved right about me."

4. Now take a step back and see how far apart Point A (taking a week off from training) and Point B (everyone knows I'm a fraud) are, in fact. This greater sense of perspective might expose to you that the only person making this training interruption calamitous is, in fact, you.

5. Sorry about that. Didn't mean to make you feel worse. It's important, though, that you recognize this is coming from your own personal demons.

Now it's time to start the journey back up. I hope that by forcing yourself through that exercise you may see that your reaction outstrips reality (is taking a time off of training really going to change how anyone thinks about you? Very likely not; in fact, those people you're worried about really aren't thinking about you that much, anyway; probably something like 30-60 seconds per week, max). With a little perspective you can start seeing the fact that your season is quite long, and a week's interruption won't change much. And if you rush back and get sick again, you've just created a much bigger and longer interruption.

We can say this to you until we're blue in the face, but what we really want is to get there alongside you. There's a great saying in coaching and teaching: "tell me and I forget; teach me and I may remember; involve me and I'll learn." What we're after, here, is mastery of your particular sport. As coaches (and, in particular, endurance coaches) there is nothing we can do for you while you're in competition. You are largely alone. What we want for you is the ability to make decisions on your own, respond to new information, and thrive no matter the environment. Learning how to deal with sickness can become a microcosm for being a better athlete. The first few times you get sick you'll want to rush back. Your coach will remind you, gently, to wait. The first few times you won't listen, and you'll be sick again in a week. Then you have a chance to take control of it yourself, owning it and taking the break you need to take. You go on to have an excellent sharpening period before that big race. You do better than you anticipated, probably due to the rest you put in while convalescing (the sporting world is full of stories like this). So that's nice, but the real benefit is that you've taken a step towards mastery of the sport.

Our author, on the verge of getting sick, feeling sick during the Chili Pie race in New Mexico