It’s Not About Going Fast

It’s about your “moderate” being fast enough

by Chris Bagg

If you’ve been to Kona, or Roth, or Nice, or 70.3 World Championships, or any major multi-sport competition, you’d be forgiven for thinking that the athletes who finish in the top ten percent are “fast.” Anyone who has seen Jan Frodeno run by or Daniela Ryf ride past will think “whoa, they are FAST.”

But actually, if you compare these GOATs to single sport athletes, they aren’t actually “fast” given how fast human bodies can actually go. If you compare Sam Laidlow’s 2:41:46 in Nice and Lucy Charles-Barclay’s 2:57:38 to professional marathoners, you’ll realize that both of them at these paces would be thought of as good amateur runners but nowhere near professional quality. Let’s keep things in France. This year’s winner of the Paris Marathon ran a 2:07 en route to his victory. That is 21% faster than Sam Laidlow’s 2:41. Those times aren’t in the same ballpark or even on the same planet. They are in the same solar system, but Sam’s time would have gotten him, oh, roughly 400th place at the 2023 Paris Marathon. We know what you’ll say next: “I’d love to see a professional runner swim and bike like those two,” and you’d be right, but that’s not what we are here to talk about. Both Laidlow and Charles-Barclay are obviously amazing athletes at the top of their respective games, but the thing we need to talk about today is what “fast” actually means in the context of triathlon (and not just long course triathlon).

Yes, given the fatigue that swimming 2.4 miles and riding 112 miles occasions, these marathon times are impressive, but they certainly aren’t “fast” when put in the context of human runners. Today we are aiming to change the focus of your training: it’s not about going fast. These athletes are champions at building their moderate efforts to a place where they are competitive at the top of the professional game. They may be fast compared to you, but they themselves are “slow” when compared to single sport athletes.

Today we want you to stop thinking about fast. We want you to start thinking about “how do I make my moderate pace quick enough that I can compete with the best in my particular division?”

What happens to your body during training?

What most athletes think is the way to train for races

A better way to think about training for races

Taking it to race day

What happens to your body during training?

When you lift your effort above a walk, or pedal harder than a light spin, or (for most people) swim at any intensity, a huge array of processes begin inside your body. Describing all of them is beyond the scope of this article (and beyond the scope of your author), but think back, way back, to the first time you ever went for a run that intended to be exercise. What happened?

First of all, your breath rate increased. Duh, you’re thinking. But really think back—those first few runs. How much did your breathing increase? When we are new to exercise, EVERYTHING is high intensity, because your body hasn’t heard that moving faster than a walk is something it needs to be able to do. Our physiologies are amazing at conserving energy, since conserving energy is a great way to ensure that you’ll actually have energy when you need it (when that lion is about to eat you, for example). So we don’t arrive in this world with robust endurance engines already in place. We have the capacity for an engine, but it’s not functional yet. We need to stimulate our bodies to prepare them for the next workout, and then the next workout after that, and then…you get the picture.

But that first time, your breathing picked up quickly, your chest tightened, and your muscles began to feel…different. Maybe they felt heavy, or as if they were “burning,” or some other uncomfortable sensation. Those feelings are your body attempting to keep up with the demand placed upon it and struggling to do so. The uncomfortable sensations are there to try and get your brain to STOP the movement that is creating the discomfort. Think about your brain like an enthusiastic five-year-old without much executive function, and your body is the sensible older sibling, reminding their younger brother or sister to chill out.

But we can change our bodies through training, which is magical, when you think about it: impose a stress on this remarkable machine we’ve been given and it will change. It’s like having a car that gets faster, or grows more pistons, if you drive it correctly. And our bodies will change differently, depending on the ways we “drive it” in training.

Let’s return to that first run. Even if that first run was quite a bit slower than our easy runs these days, years later, since it was new it was a huge surprise to your system, and you probably didn’t feel very good when you ventured out on that run. This early discomfort is why many new athletes give up: the first few runs feel terrible, and unless you have some goal that appeals to your enthusiastic five-year-old brain, that brain will most likely lose interest, much in the same way that five-year-olds lose interest. The price of admission is too high, and the payoff seems vague.

But you didn’t lose interest, for whatever reason, and you kept running (or cycling, or swimming, or rowing, or skiing). Maybe you liked the people you picked up the activity alongside. Maybe you liked the idea of yourself as endurance athlete. Maybe your parents wouldn’t let you quit the swim team (oh, how did that example get in there?). In any case, you persevered.

What changed? Now think back not to the first run, but maybe the 30th or 40th. You’ve been running for a couple of months, and now there is some discomfort when you start, but unless you really try to run quickly, the discomfort fades in the first few minutes to a manageable, low-grade discomfort, and the feeling of being outside, moving your body, and then the sweetness of completion have begun to outpace the discomfort of the activity. Your body has changed, but how?

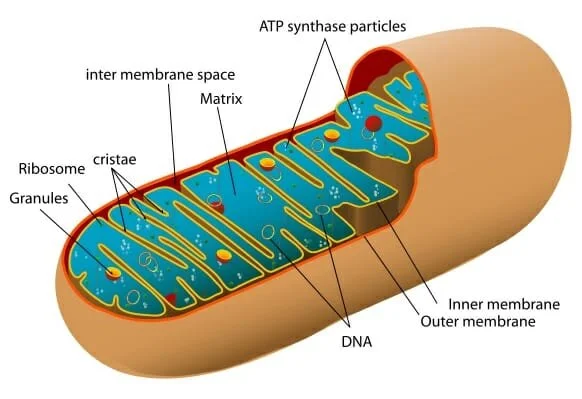

When you first start training, your body isn’t very good at moving oxygen, the currency of exercise, around. Exercise science is fantastically complicated, but we can simplify things to the point of: you inhale oxygen into your lungs; your heart moves blood past your lungs in a way that oxygen can move into your blood; your arteries and capillaries (tiny blood vessels) transport that oxygen to the muscles that are working; the cells in those muscles absorb oxygen (absorb isn’t quite right, but it’ll suffice in this instance) and get the oxygen to little organelles called “mitochondria;” the oxygen in the mitochondria is used, alongside carbohydrates or fats, to create something called Adenosine Tri-phosphate (ATP), which powers muscle contractions and allows you to move. That process creates carbon dioxide (among other byproducts), which then experiences the reverse process that inhaled oxygen did, and eventually you exhale that CO2 into the atmosphere.

We can boil this down even further: oxygen powers muscular contractions. The more oxygen we can transport, the more ATP we can produce. So more oxygen = more muscular contractions = being able to run/bike/swim/row/ski faster.

When we start training, though, our ability to transport oxygen, frankly, kinda sucks. So even a light run for someone who is sedentary feels like they are sprinting. Remember that fact the next time you take your off-the-couch buddy for a bike ride—their body is vastly different from yours, simply because they haven’t run much oxygen through their system. If they run three times a week for 12 weeks, you will be very surprised at how much easier the running seems to them when you run with them again. These athletes are in the sweet phase of “noob gains,” when ANY kind of training makes them better, because ANY training demands more oxygen transport than their body is used to, so their physiology is constantly trying to catch up with the stress and adapt.

Sadly, though, this process begins to wane after a point. Maybe your friend never runs more than 30 minutes each time they run, and never more than three times a week. Eventually, the body can handle this stress just fine, and the athlete stops improving. This is the principle of accommodation, and it applies at every level of sport, beginner to GOAT.

So the equation is simple but not easy: you need to increase the stress on your physiology if you want to keep improving. You need to find ways to increase the amount of oxygen your body can deliver to the working muscles (again, this is a vast oversimplification—if there are inefficiencies in the way you move your body, just adding more oxygen might not make you faster, but we’re attempting to communicate broad ideas today).

Parker Valby, 2023 NCAA XC Champion, only runs 2-3x/week

workouts are not rehearsals

Once athletes understand this, they face a fork in the road. They understand that they need to improve their bodies’ abilities to absorb and transport oxygen. But since we are endurance athletes, we probably have a “if some is good, more is better” mindset. It becomes easy to believe the best way to improve oxygen transport is to run as much as possible through the system in the shortest unit time. You’re time-crunched, right? If there were a way to get the benefit of a 60-minute run in 30-minutes, you should do that, right? If you can run 40 ml of oxygen through your body each minute at the pace it takes you run a mile every ten minutes (400ml over that period), couldn’t you accomplish the same goal by running 60ml through your system in slightly less than 7 minutes? And also, if I want to be able to run 7:00/mile in my upcoming half-marathon, shouldn’t I run as much time as possible at 7:00/mile? Isn’t doing anything unspecific going to be a waste of time?

This approach is common, and it makes sense. It stands to reason that if you want to do something a certain way, isn’t the best way to practice for achieving your goal to mimic the goal exactly? Specificity is important, and there is even a principle of specificity which states:

The way the body responds to physical activity is very specific to the activity itself.

This principle, while true, can give rise to some counter-intuitive behavior, however. We have heard, many times, that an athlete who is preparing for an iron-distance race wants to run a marathon as part of their preparation. This way of thinking makes total sense, but begins to break down if you examine it more carefully. If we strive to be specific in all things related to our training, shouldn’t we only be running a marathon every time we want to go out and train for our Ironman?

Clearly, no. Only running 26.2 miles each time we go out for a run is ludicrous, and will only end in injury. So that example can show us that, although specificity is important, it’s obvious that specificity shouldn’t be our only goal. If you want a real-world example, Parker Valby, the women’s 2023 NCAA XC Champion (and NCAA 2023 5000m champion) usually only runs 2-3x per week due to the injuries that are typical of elite runners. How does she close the gap (or, actually, establish the gap, since she’s winning) even though rarely coming close the large volumes most elite runners log? Through cross-training, which is the opposite of specific. She deploys the arc trainer, elliptical, and pool sessions to keep her conditioning extremely high, and then runs specific sessions when she needs them.

So what SHOULD be our goal, if specificity all the time isn’t sensible?

workouts provide stimulus, not rehearsal

The first cycling coach I ever had always said “when you’re out riding, that’s not training. That is stimulus. Training happens when you are lying on the couch, recovering from the session.” He was totally right. When you are working out, you put your body under strain. Your body changes to accommodate that strain. So if we want to change the body, we need to give it something new to do. When we are talking about endurance training, “new” usually means “more” of something, but it can also be working on swim technique, challenging your body’s mobility in a new way, or thinking a different way while we are training. Before you run off, however, and start doing something new in every session, please hear us: NOT EVERY WORKOUT SHOULD BE NEW. Many workouts are maintenance sessions: they simply keep you from regressing by keeping the training load consistent. So maybe in a 12-13 workout week for multisport athletes, 9-10 of them are sessions that simply reprise the intensity and duration of what we have done before, and 2-4 sessions per week move the needle to an intensity or duration we haven’t worked on before.

This pattern holds at the mesocycle level, too (a training block of 3-6 weeks). Each mesocycle should progress from the previous one, so the body is almost always playing catch up. This consistent game of catch up is called “progressive overload” and simply means that we aim to stress the body slightly more than its current capacity for work each cycle. Then we build in periods of recovery (lying on the couch, both literally and figuratively) that allow the body to “train” and change so it can handle this new work load. That is how endurance training works.

So how does this help us achieve our gains in a more effective manner? If you can think about your training being a “dose,” rather than a rehearsal, it’s easier to think about training as assembling a large pyramid of workouts, a series of doses that add up to something far greater than any individual session.

Those athletes who are going hard all the time, or always aiming for specificity? They build a tower of fitness, rather than a pyramid. What’s wrong with a tower? It’s not as stable, and you can’t build it as high as a pyramid (this metaphor begins to break down once things like modern building materials such a steel begin to enter the picture, but hopefully you see what we’re getting after).

Some of your workouts are maintenance workouts: these are bread-and-butter sessions that probably occupy something like 85-95% of your weekly training time. They should be fairly easy to moderate—like 3-5/10 on the classic 1-10 RPE scale. You should be able to have a conversation while doing them. You should be able to focus on plenty other than your workout. These workouts maintain the fitness you have, and, if you’re working with a good coach or self-coaching effectively, the total time you spend doing this work should go up slowly over the course of your season, like the stock market. Remember that principle of progressive overload? It holds here, too. By steadily adding a little volume most weeks (NOT all weeks) you give your body a low-grade challenge to keep up and adapt, which helps. These consistent doses of training achieve all of the goals we pointed out above: more capillaries to transport oxygen; greater fat oxidation (better “fuel” economy); more mitochondria in the cells of your working muscles.

A very small amount of your training is “quality” or “high-intensity” or “key” (although we don’t like the term “key” since it suggests that the other workouts are not key, when actually the lower-intensity sessions are MORE important). These sessions are even LESS specific than the low-intensity ones. When was the last time you saw anyone perform a marathon as a series of 400m intervals with 100m walks in between? But what they do is challenge your body to move truly fast for you, so that your body realizes that running or riding or swimming faster is something you are trying to do. This is where the magic of the lower-intensity work appears. That lower intensity work has improved your body’s ability to transport oxygen, burn fat instead of carbohydrate, and increased the sites of aerobic and anaerobic respiration in your cells. Here’s another metaphor: the untrained athlete is like a single-lane highway—a limited number of cars can travel on it, so its throughput is limited and average speeds of traffic will be lower. An athlete who has done a large volume of low intensity work has 1) expanded the lanes of traffic so it is more like a super-highway, 2) improved the surface of the road so vehicles have greater economy, and 3) built more factories at the end of the highway, so more products can be built. The untrained athlete is what we call “rate-limited.” There is a cap on the amount of speed that is possible. The highly trained athlete is not rate-limited, and since more deliveries of oxygen are possible, and there are more “factories” to process that oxygen, the entire process (running, riding, swimming, rowing, skiing, whatever!) goes faster.

If your high-intensity workouts are faster, then YOU will become faster, provided you continue to do your lower-intensity work.

If you become faster, then ALL of your other speeds become faster, also (as long as, you guessed it, you continue to do your lower-intensity work).

I think we need an example.

At the beginning of the season in which she is training for a marathon, Melanie runs a 10k as a test workout. She runs it as hard as possible and logs a 45-minute time. Given that performance, we would set her pace zones as follows:

ZR: 8:55-9:50

Z1: 8:20-8:45

Marathon Pace: 7:55-8:15, or 3:27-3:36

Z2: 7:55-8:19

Z3: 7:25-7:54

Z4: 6:50-7:24

vVO2: 6:20-6:30Three months into the season, Melanie repeats the test workout, running a 43:00 10k. She has been diligently running easy most of the time, with once-weekly track sessions and then steadily increasing threshold intervals. Her zones are now as follows:

ZR: 8:35-9:25

Z1: 8:00-8:34

Marathon Pace: 7:35-7:50, or a 3:18-3:25

Z2: 7:35-7:59

Z3: 7:03-7:34

Z4: 6:33-7:02

vVO2: 6:00-6:10

Simply by training effectively, Melanie has improved her “moderate” pace (slightly above what we call Z1 but still well below threshold) by almost ten minutes. Her new normal is a faster moderate.

Taking “moderate” to the race course

When you get to race day, you should not be hoping for anything magical. Sorry, but race-day magic is something of a myth. You really can’t expect to do anything except express the training you have done leading up to your event. Thinking otherwise is magical thinking, and will end in ruin.

If you have trained well, you know what pace and heart rate and power are your “moderate” intensities. Those moderate intensities are the ones you will race your iron-distance races at, and probably your half-ironman races, too. Does this mean that races won’t feel “hard?” Sadly, no. These races are long, and doing anything at a moderate effort for a long period of time will eventually feel quite hard. But a steady, achievable effort will always be faster than the “fly and die” approach, where an athlete mistakenly believes that by “putting time in the bank and hanging on” they will have a good race. This is a strategy born of fear, and those fear-based strategies are rarely successful.

Conclusion

If you stuck with us for this, we’re impressed! Reading can take some endurance, too. But maybe that’s a new leaf you are turning over, as you realize that a long, deliberate approach may serve you better than frantically trying to cram at the last minute. Many athletes come to us saying that their big goal is to feel strong for the entire run portion of their triathlon. The secret to achieving that goal?

Make your moderate faster, rather than trying to go fast.